Toni “Tone” Mikulka-Chang

Founder of ArtJoy.org

GVNC Cultural District: What is your medium?

Mikulka-Chang: My medium is culture-making—the choreography of materials, meaning, and participation until a temporary community forms and a place feels more alive, more itself. I’m the founder of ArtJoy.org, and my practice lives where art becomes a social technology: workshops, parades, installations, and performances that invite people not to consume art, but to enter it.

On the surface, my mediums are tangible: clay, sculpture, lantern-making, papier-mâché, fiber arts, hand-painted silk (flags, kites, and large-scale environments), giant puppets, wearable forms, and the moving body. But beneath that, my medium is the ecosystem that makes art function as a public good: the classroom and rehearsal, the learning mind, the skilled hand, the crowd that becomes a cast; the drawing board, the website build, the outreach, the grant, the logistics, the small-business scaffolding that allows wonder to arrive in the world—safely, beautifully, on time.

This is why arts and cultural leaders often bring me in to activate civic outdoor spaces with large-scale performance art—turning plazas, parks, and main streets into living stages and shared mythologies that deepen placemaking, amplify local cultural identity, and strengthen the connective tissue of a vibrant arts community. Alongside the spectacle, I teach workshops and build symbiotic collaborations with other artists—most recently an upcoming partnership with Marya Stark to create a new giant puppet work for her She Rose show.

Since moving to Nevada City, my work has taken a distinctly local flight: giant, hand-painted silk bird-kite puppets, butterflies, and dragonflies inspired by the species along the Yuba River—forms that make ecology visible at human scale and invite people into an intimacy with place. If you’ve ever wanted to walk through a forest of silk wings, follow a dragonfly the size of a small car, or join a parade that feels like a spell—that’s the world my medium is built to hold.

GVNC: At what point in your life did you realize your calling?

Mikulka-Chang: My calling didn’t arrive as a single epiphany. It revealed itself as a pattern—recurring across materials, communities, and landscapes—until it became unmistakable: I am drawn to the places where art becomes ritual, where making becomes belonging, and where objects become carriers of story.

The earliest signs were literal and embodied. I began performing with puppets at five years old near New York City—less interested in “putting on a show” than in the strange social alchemy that happens when attention gathers and a temporary world becomes real. At fifteen, clay arrived and stayed. Pottery taught me a foundational truth: transformation is not metaphor; it is physics. Pressure changes matter. Time changes matter. Fire changes everything.

When I later studied Anthropology and Art at a public university in the Adirondack region of upstate New York, that intuition became a framework. My studies focused on human evolution, culture and belief—ritual, symbol, and the ways meaning is made and transmitted. I became captivated by a deep historical fact: some of the earliest fingerprints of “civilization” are not written laws or monuments, but made things—clay vessels, figurines, painted surfaces, masks, pigments, and ceremonial objects. Pottery is not merely utilitarian storage; it is often a record of cognition: pattern, abstraction, repetition, cosmology. It marks a shift in how humans relate to time (planning, storing, preserving), to place (settling, returning, building), and to one another (sharing meals, exchanging gifts, burying the dead, honoring the sacred).

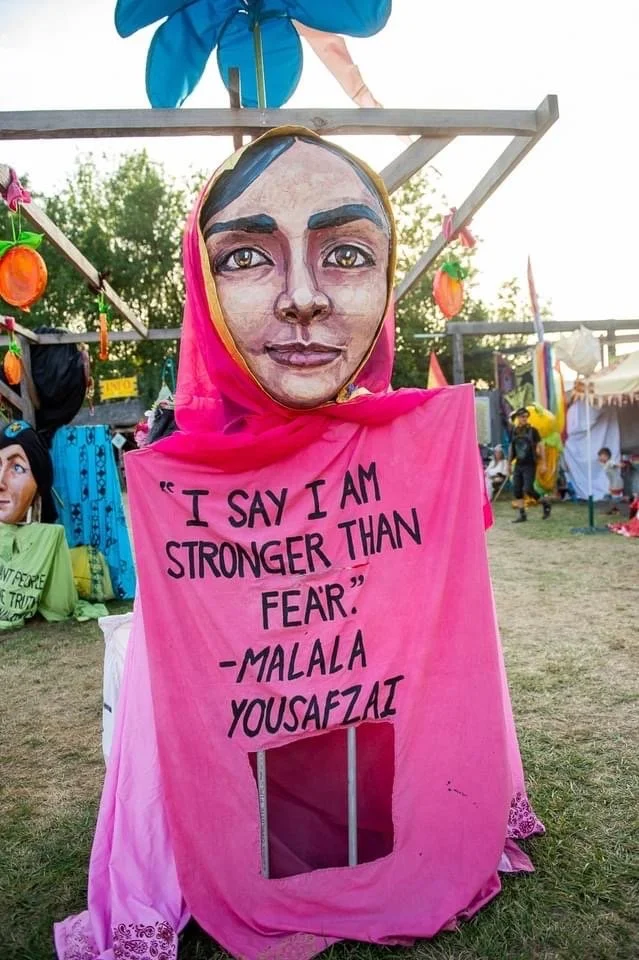

Mask making and ritual objects carry a similar signal. Across cultures, masks are not “costumes” in the trivial sense—they are technologies of transformation. They allow a person to become an ancestor, a spirit, an animal, a deity; they mark thresholds—initiation, mourning, harvest, renewal. In anthropology, you learn to read these not as curiosities, but as infrastructure for meaning: artifacts that organize social life, belief, and belonging. When I began making puppets, lanterns, and large-scale performance forms, it felt less like inventing something new and more like joining an ancient lineage of human behavior: shaping matter into a vessel for story, and story into a vessel for community.

Two theorists helped me articulate how all of this cohered.

Margaret Mead taught me to understand culture as learned, patterned, and therefore makeable. Her work pressed me to see that what we call “community” is not merely a demographic fact—it is a practiced reality, built through repeated rituals of attention, care, and participation. This profoundly shaped how I teach. In my workshops—especially with children and families—I’m not just teaching technique. I’m building micro-cultures of permission: spaces where curiosity is honored, collaboration is modeled, and embodied learning becomes a civic value. My years leading programming in a children’s museum later confirmed this: early childhood is not a prelude to culture. It is one of culture’s primary engines.

Claude Lévi-Strauss offered another vital lens: structure. He illuminated how societies organize meaning through relationships—how symbols and oppositions stitch the visible world to the invisible one, turning experience into shared intelligibility. That idea shaped how I build large-scale public work. Giant puppets, lanterns, and hand-painted silks are not merely objects; they function as symbolic infrastructure. They make complex themes legible in a glance: wing and riverbank, fire and care, predator and pollinator, wildness and responsibility. In a public space, this matters. People don’t need prior knowledge to “get it.” They need a body, attention, and a willingness to participate. The form itself becomes an invitation into meaning.

In 2009, a major life change sent me into an apprenticeship pilgrimage to Bread & Puppet Theater in Vermont, where I trained in giant puppet making and learned stilt walking. That experience sharpened a principle I now rely on constantly: scale changes people. When something becomes larger than the individual, it requires collective coordination—multiple hands, shared timing, a kind of temporary social organism. With my background as a state champion lacrosse player, the rod-and-stick choreography of giant puppetry felt like a perfect synthesis of my instincts: disciplined movement, precise teamwork, and the exhilaration of bodies moving as one.

In 2010, my first Burning Man widened the “field site” even further. Surrounded by visionary artists and collaborative makers, I witnessed temporary culture built in real time—how aesthetic worlds function as social worlds, with their own ethics, rituals, economies of labor and gift, and deep norms of mutual reliance. That current led me through the West Coast festival circuit and into the Pacific Northwest, where I eventually ran a community arts workshop with the Fremont Arts Council in Seattle. There—supported by grant funding and mentorship—Giant Puppets Save the World was born: a project shaped by the practical anthropology of building community through shared making.

From there, the work kept proving itself: performances, youth programs, teaching giant puppet making and stilt walking, and repeated invitations into community contexts where art served as a gathering practice. At the Oregon Country Fair I met my husband, Joey Chang (CelloJoe), and the work became not only a vocation but a partnership—music and movement braided into the same civic fabric.

There was a later chapter back in New York City—set design, large-scale installations, and proximity to the machinery of spectacle. But the deeper pull—toward nature, participatory art, and communities that still know how to gather—brought us to California, where we lived in Berkeley for twelve years before moving to Nevada City in 2022.

Pottery remained a constant through every chapter. Clay is my grounding medium and my first teacher: it trains attention, humility, patience, and the ability to collaborate with material reality. During the pandemic, pottery became a kind of lifeline and I launched Yoga Pottery—a practice and a teaching project that braided somatic awareness with making, as I earned my yoga teacher certification online. It was chaotic, heartfelt, and strangely perfect: a reminder that the studio can be a sanctuary, and that the simplest ritual—hands in mud, breath in body—can repair the nervous system and restore the will to create.

Today, anthropology still keeps me accountable to context. I don’t import a “show” into a place; I build work that listens to local ecology and local identity. Since moving to Nevada City, my practice has expanded into giant, hand-painted silk bird-kite puppets, butterflies, and dragonflies inspired by the species along the Yuba River. This isn’t decoration. It’s public storytelling that says: this place matters, and its living systems are worthy of wonder.

And I hold the practical truth that many artists know: the work is inseparable from the infrastructures that sustain it. My medium includes mud, paste, silk, water, color, and air—but also teaching, outreach, fundraising, grant-writing, web-building, logistics, and the daily discipline of small-business ownership. If my anthropology studies taught me anything enduring, it’s that culture is made—again and again—through repeated practices. My calling is to design those practices so art becomes a commons: something we build together, and therefore belong to together. ArtJoy.org is the culmination of all of this.

GVNC: Tell us about your creative process.

Mikulka-Chang: My creative process starts with curiosity and a feeling: what kind of experience do I want people to have together? Wonder, laughter, tenderness, awe, mischief, reverence—sometimes all in one afternoon. I’m building not just an object, but a moment people can step inside.

A spark + a “why.”

I begin with a hook: a species, a story, a local place, a theme (pollination, fire, water, community care). I jot down the emotional goal and the simple invitation: Do I want people to follow it? Hold it? Dance with it? Build it with me?Moodboard meets sketchbook.

I collect images, colors, textures, and movement references—then I sketch fast and messy. I’m not looking for perfection; I’m looking for aliveness. If it’s going to fly or be puppeteered, I’m already thinking about silhouette, scale, and how it reads from 50 feet away.Clay first, because it tells the truth.

Clay is my favorite way to “think.” I’ll often sculpt a head, mask, beak, or face first—because once a character has a presence, everything else locks in. Clay gives me proportion, expression, and the feeling of the piece before it exists.Build the bones, then the magic.

I move from sculpture to structure: bamboo, reed, rods, handles, harnesses—whatever gives the piece strength and good movement. Then comes papier-mâché, silk, fiber, paint, and all the details that make it feel mythic and alive.Test it in the real world.

I do quick prototypes and “wind tests.” I check balance, weight, visibility, safety, and how it moves with a body inside it or hands on the rods. I tweak until it feels effortless—like it wants to dance.Rehearsal turns it into a living creature.

A puppet isn’t finished until it moves. I practice with puppeteers and performers: breath, timing, gaze, lift, rest. The goal is to make it feel like a being—not a prop.The community is part of the artwork.

Workshops aren’t an add-on—they’re part of the piece. I love the moment when someone who swears they “aren’t an artist” suddenly realizes they just helped build something beautiful. That confidence and shared ownership is the real engine.Release it into the world.

Then we bring it into public space—parks, plazas, streets, riverbanks—where light, weather, music, and surprise become collaborators. The best moments are always unscripted: a kid reaching up, a crowd parting, a spontaneous parade forming.

So yes, I sketch and sculpt and paint—but the real process is: spark → build → test → rehearse → invite people in → let it become bigger than me.

GVNC: What inspires you?

Mikulka-Chang: I’m inspired by the moment when ordinary life tips into wonder—when a street becomes a stage, a crowd becomes a chorus, and people remember they’re allowed to play.

Nature is a primary collaborator: the Yuba River watershed, wind and water, seasonal light, and the local species that feel like living symbols—birds, butterflies, dragonflies, pollinators. I’m endlessly moved by their engineering, their resilience, and their beauty, and I love translating that into giant silk wings and moving sculptures that make ecology visible and felt.

I’m also inspired by ancient human creativity—pottery, masks, lanterns, ritual objects—the oldest evidence that humans have always used made things to hold meaning, mark transitions, and tell stories bigger than any one person. Clay, especially, keeps me honest: it’s humble, elemental, and unforgiving in the best way. It reminds me that transformation is real and earned.

Community is my other deep inspiration: the bravery of beginners, the collective rhythm of people making together, and the peculiar magic that happens when collaboration clicks. I’m drawn to artists and cultural leaders who build worlds—visionaries who blend beauty with purpose—and to partnerships that create something neither person could make alone (like my ongoing collaborations and new projects with fellow artists).

And finally, I’m inspired by joy as a civic force. Not “happy for a minute,” but the kind of joy that strengthens the nervous system, opens the imagination, and makes connection feel possible again. That’s the fuel. That’s the north star.

GVNC: What are you most proud of?

Mikulka-Chang: I’m most proud of building a body of work that makes people feel brave—brave enough to make something with their hands, to move in public, to collaborate, to be seen, and to belong.

On a practical level, I’m proud of founding ArtJoy.org and growing it into a platform for immersive workshops and large-scale performance art—work that arts and cultural leaders trust to activate public spaces and strengthen community. I’m proud of the worlds I’ve helped bring to life through Giant Puppets Save the World: giant flying silk birds, butterflies, dragonflies, lantern processions, puppets, masks, and collaborative builds that transform a park or street into shared myth for a day.

I’m also proud of my hand puppetry performances, especially the kid-focused storytelling that sparks laughter, imagination, and participation—often becoming the on-ramp that invites families into the bigger world of puppets, artmaking, and play.

And I’m proud of keeping pottery at the center of my life through every chapter—building Yoga.Pottery as a teaching practice, and growing my ceramic work through opportunities to teach at The Center for the Arts, The Foundry, Curious Forge, Studio 540, and more here in Nevada City. Getting to exhibit my pottery and show my work publicly has been deeply meaningful too—each show feels like a milestone in a lifelong relationship with clay.

I’m especially proud of the teaching—because that’s where the quiet miracles happen. Watching a child step into imagination with total confidence, or watching an adult who “isn’t an artist” suddenly realize they are… that moment of self-recognition is everything.

And finally, I’m proud of the often-invisible infrastructure behind all of it—planning, grants, outreach, partnerships, and the daily discipline of small-business logistics—that allows big, joyful public art to actually happen.

GVNC: What do you love best about our creative community?

Mikulka-Chang: I love how genuinely participatory our creative community is—people here don’t just attend art, they make it, volunteer for it, teach it, learn it, and show up for each other across disciplines. There’s a rare combination of high craft and low ego: serious skill, real curiosity, and a willingness to get messy, collaborate, and try something new.

I love the way the land and the art scene are in constant conversation. The rivers, forests, light, and seasons don’t just “inspire” work here—they shape the pace, the materials, the themes, and the gatherings. There’s a shared reverence for place that makes creativity feel rooted instead of performative.

And I love the density of connectors—artists, producers, venue partners, teachers, builders, makers, musicians, and community organizers—who are constantly weaving new relationships. In Nevada County, it’s normal for a show to become a workshop, a workshop to become a parade, and a parade to become a long-term collaboration. That spirit of mutual uplift—people championing each other’s projects, sharing resources, and making room for newcomers—is what makes the whole ecosystem feel alive.

GVNC: Name two Nevada county artists you admire and why.

Marya Stark — I admire the way she blends songwriting, voice, and visual world-building into performances that feel both intimate and mythic. Her work carries emotional precision and spiritual grit, and she creates shows that feel like a shared ritual rather than a “set.” I also respect her commitment to collaboration—she makes room for other artists inside her vision.

Glen Husted — I admire his sculpture practice for its captivating, dynamic forms that explore texture and natural elements with a tactile, organic intelligence. His work fuses abstract shape with earthy tone and rough-hewn surfaces that carry a raw beauty—modern and primal at once—inviting viewers to slow down and truly read form, weight, and balance. I also deeply respect his leadership as the force behind Indian Springs Art & Ceramic Center (ISACC) in Penn Valley, and the visionary future he’s building there for artists, makers, and the ceramic community.

GVNC: What’s coming up for you?

Mikulka-Chang: We have a lot happening! Workshops, classes, parades, festivals and fairs! See details below:

February 2026

Nevada City Mardi Gras Parade & Street Fair — Sunday, February 15, 2026

Street Fair 12:00–4:00 PM; Parade 2:00 PM (downtown Nevada City)

NYC Toy Fair (Javits Center) — Monday, February 16 – Tuesday, February 17, 2026

Show runs February 14–17, 2026 (ArtJoy will be there from the 16th–17th)Star Tetrahedron Lantern-Making Workshop (ArtJoy Hub) — Friday, February 28 & Satuday, March 1, 2026

ArtJoy.org HQ, 104 New Mohawk Rd, Nevada City • 2 days (~2.5–3 hrs/day) • $125/person • limit 10

March 2026

Puppet Playtime (The Center for the Arts) — Saturday, March 7, 2026 • 10:00–11:00 AM

Ages 0–7 with caregivers • 15-min show + puppet playground (100+ hand puppets)Puppet Playtime (The Center for the Arts) — Saturday, March 14, 2026 • 10:00–11:00 AM

Ages 0–7 with caregivers.Giant Puppet Creation Lab: The Rose Devaa with Toni Mikulka-Chang + Marya Stark (Grass Valley Museum and Cultural Center)

March 16–21, 2026 • 10:00 AM–4:00 PM daily • limit 15 • Collective build of a touring ceremonial giant puppet + embodiment/performance arc.Bioneers Conference (Berkeley, CA) — March 26–28, 2026

June 2026 (The Center for the Arts – ArtJoy WonderWorks camps)

Puppet & Story Makers Summer Camp 2026 (The Center for the Arts, Grass Valley)

June 15-19, 2026 • 12:30–3:30 PMClay & Discovery Summer Camp 2026 (The Center for the Arts, Grass Valley)

June 22–26, 2026 • 12:30–3:30 PM

July 2026

High Sierra Music Festival (Grass Valley / Nevada County Fairgrounds)

July 2–5, 2026Oregon Country Fair (Veneta, OR) — July 10–12, 2026

Clay & Discovery Summer Camp 2026 (The Center for the Arts, Grass Valley)

July 20–24, 2026 • 9:00 AM–12:00 PMPuppet & Story Makers Summer Camp 2026 (The Center for the Arts, Grass Valley)

July 27-31, 2026 • 9:00 AM–12:00 PM

GVNC: Please share where how our readers can get ahold of you and find out more about your work.

www.artjoy.org

Instagram: @GiantPuppetsSavetheWorld

Facebook: @GiantPuppetsSavetheWorld

www.yogapottery.com

Instagram: @Yoga.Pottery

Stay connected and feel free to reach out via email to work with Toni at GiantPuppetMaven@Gmail.com

This story originally appeared in the February 2, 2026 edition of the GVNC Culture Connection newsletter.